Moment of Revelation:Mao Zedong's Loyal Subject Zhou Enlai (Complete Version)

On June 27, 1981, the 6th Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China passed the “Resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Several Historical Issues of the Party Since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China,” in which the evaluation of Zhou Enlai, former Vice Chairman of the CCP and Premier of the State Council of China, was “infinite loyalty to the party and the people, devoted and diligent,” and praised him for “maintaining the overall situation” during the “Cultural Revolution.” On February 29, 2008, then General Secretary Hu Jintao praised Zhou Enlai for “bearing humiliation and heavy burdens” during the Cultural Revolution at a symposium commemorating the 100th anniversary of Zhou Enlai’s birth.

Author | youtube

For readability, this website editor has made appropriate modifications without deviating from the original meaning! At the same time, this article only represents the author’s views; this website merely presents it to help readers gain a comprehensive understanding of historical truths!

On June 27, 1981, the 6th Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China passed the Resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Several Historical Issues of the Party Since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China, in which the evaluation of Zhou Enlai, former Vice Chairman of the CCP and Premier of the State Council of China, was: “infinite loyalty to the party and the people, devoted and diligent,” and praised him for maintaining the overall situation during the Cultural Revolution.

On February 29, 2008, then General Secretary Hu Jintao praised Zhou Enlai for “bearing humiliation and heavy burdens” during the Cultural Revolution at a symposium commemorating the 100th anniversary of Zhou Enlai’s birth. In today’s declassified moment, Voice of America will demonstrate to you exactly to whom Zhou Enlai was loyal and what his “maintaining the overall situation” and “bearing humiliation and heavy burdens” truly referred to.

Zhou Enlai’s Personal Struggles

On September 20, 1975, outside the operating room of the 305 Hospital of the Beijing People’s Liberation Army, Zhou Enlai was slowly being pushed into the operating room. However, even China’s top doctors at the time felt powerless. Zhou Enlai’s cancer cells had already metastasized, and his life was nearing its end. As he was being pushed through the corridor towards the operating room, Deng Xiaoping, Zhang Chunqiao, Deng Yingchao, and Wang Dongxing were all present. As he approached the operating room, Zhou Enlai shouted: “I am loyal to the party and the people; I am not a surrenderist.” At that time, Deng Yingchao instructed Wang Dongxing to report this statement.

China was then in the ninth year of the Cultural Revolution, with politics still in turmoil and the economic situation worsening. At this time, Zhou Enlai was the number two figure in the Communist Party of China, second only to Mao Zedong, and above all others. But before undergoing a major surgery with uncertain outcomes, this Chinese Premier was most worried about losing the trust of the Chairman of the Communist Party of China, Mao Zedong, and being seen as a surrenderist.

At the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, many central and provincial leaders, including Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, were criticized and persecuted, so Zhou Enlai was very nervous because the world was in chaos and the political winds were turbulent. Zhou Enlai felt that something might go wrong at any time, so he had Deng Yingchao keep a suitcase in the Xihua Hall office with his personal toiletries inside, prepared to take it if he was arrested.

What troubled Zhou Enlai was an old case that had occurred exactly 40 years earlier. In February 1932, after the failure of the first cooperation between the Kuomintang and the Communist Party, several Shanghai newspapers published a “Notice of Withdrawal from the Communist Party by Wu Hao and Others,” with Wu Hao being a pen name Zhou Enlai used since his student days. At that time, including Zhou Enlai, 243 Communist Party members announced their withdrawal from the party, causing considerable shock. It was later proven that the Wu Hao incident was a scheme planned by Zhang Chong, the head of the Kuomintang Central Organization Department’s Investigation Division, to sow discord within the Communist Party. Mao Zedong was well aware of this. At that time, Mao Zedong was the Chairman of the Chinese Soviet Republic in 1932, and he issued a special announcement stating that this was a Kuomintang rumor and slander.

However, during the Cultural Revolution in 1967, the Wu Hao incident resurfaced. On May 17, 1967, Jiang Qing wrote a letter to Lin Biao, Zhou Enlai, and Kang Sheng, attaching the notice. Jiang Qing wrote in the letter: “On the night of May 12, we received a letter from Zhou Rongxin’s daughter Zhou Shaohua and the Red Guards from Tianjin Nankai University to the Central Cultural Revolution Group, saying that they had discovered an anti-Communist notice, led by Wu Hao Zhou, requesting a face-to-face interview with me.”

The former National Defense University of the People’s Liberation Army provided a different account of Li Wenqing and former Air Force Commander Wu Fangxian’s recollections. Li Wenqing, who had served as the secretary to the former Nanjing Military Region Commander Xu Shiyou, said in his recollections that on May 4, 1968, Xu Shiyou, while investigating the rebels, found a newspaper with the “Notice of Withdrawal from the Communist Party by Wu Hao and Others” and personally handed it to Mao Zedong. Mao Zedong, during a meeting with members of the Central Cultural Revolution Group and several Vice Premiers on May 8, said: “People like Xu Shiyou, who are over 60, don’t know about the Wu Hao notice; this is fabricated by the enemy.” Zhou Enlai was also present at the time.

However, Mao Zedong, who was well aware of the ins and outs of the matter as early as 1932, left the case unresolved. Mao Zedong’s statement was: “Comrade Lin Biao should read this and then ask the members of the Cultural Revolution Group to read it, keep it, and mark it with two red lines.” So, after the Wu Hao incident, it became a sword hanging over Zhou Enlai’s head, used as a tool to threaten and suppress him.

According to the official Chinese publication “Zhou Enlai Biography,” Zhou Enlai spent ten days writing that speech, making a severe and relentless self-analysis, and even excessive criticism. Among the various line errors Zhou Enlai admitted to, the Ningdu Conference held by the Central Bureau of the Soviet Area in 1932 was called “the biggest mistake and sin in his life.” The Ningdu Conference was a critique of Mao, and the harshest critics of Mao were the people in the rear Central Bureau like Shi Zhe and Gu Zuolin, who had already passed away, but this debt remained with Zhou Enlai.

At the Ningdu Conference, Zhou Enlai replaced Mao Zedong as the Political Commissar of the First Front Army of the Red Army and led the Red Army to victory in the Fourth Encirclement and Suppression Campaign. This made Mao Zedong’s words neglected. Mao Zedong had always been resentful of Zhou Enlai. Zhou Enlai reviewed this during the Yan’an Rectification Movement and essentially bore the blame for a lifetime, being accused of usurping the military. The accusation of Zhou Enlai usurping the military was completely groundless. Zhou Enlai had served as a member of the Politburo Standing Committee of the Communist Party Central Committee in 1928. In 1933, Mao Zedong only became a member of the Central Politburo of the Communist Party of China. Zhou Enlai began serving as the Secretary of the Central Military Commission of the CCP in 1931, while Mao Zedong was then only serving as the Chief Political Commissioner of the First Front Army of the Red Army. At that time, Zhou Enlai’s status in the CCP’s military was far higher than Mao Zedong’s.

In reality, Zhou Enlai had been in a very high position within the CCP for quite a long period. After the failure of Zhang Guotao’s Great Revolution, he became the highest leader of the CCP’s military work. Mao Zedong’s role as the Chief Political Commissioner of the Red Army was also recommended by Zhou. When Zhou Enlai arrived in the Soviet area, his position was the Secretary of the Central Bureau of the Soviet Area, and he made major decisions regarding the military. Therefore, when Zhou arrived at the army from Shanghai and to Jiangxi, he was effectively Mao Zedong’s superior.

Even at the Zunyi Conference, which the CCP claimed established Mao Zedong’s leadership position within the party, Mao Zedong was only elected as a member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo under Zhou Enlai’s full recommendation, and the decisions were still made by the highest military leader Zhou Enlai as the military commander. Zhou Enlai was the party-appointed person responsible for the final decisions on military command, with Mao Zedong serving as an assistant to Zhou in military command. Later, a three-person military command group was established, with Zhou Enlai as the leader and Mao Zedong and Wang Jiaxiang as members, and Zhou Enlai remained Mao’s superior.

The process by which the top military position was transferred from Zhou Enlai to Mao Zedong remains unclear. In simple terms, during the Zunyi Conference, Zhou was still the final decision-maker. Mao Zedong began by assisting Zhou Enlai. Mao’s ability was very strong, while Zhou Enlai’s position seemed somewhat uneasy. He felt that he could not control the entire situation. When the First Front Army and the Fourth Front Army met, there was a severe confrontation between Mao and Zhang Guotao regarding whether to go north or south. At this time, Zhou Enlai was suffering from a liver abscess, had a high fever, and was almost dying from illness. Thus, during this process, Mao naturally took over the power.

Mao Zedong and Zhang Wentian convened the Standing Committee meeting in Zhou Enlai’s absence and decided that Mao Zedong would be responsible for military affairs. Zhou Enlai did not attend the meeting at that time but had already begun to actively concede, believing that Mao Zedong had a better way to handle these issues. In other words, Zhou Enlai did not insist on fighting. He also felt that Mao Zedong was more capable.

After arriving in Shanbei, Mao Zedong hoped to push Zhou Enlai out of the army and assign him to local work. Zhou Enlai at that time expressed that he would continue to stay in the army as Mao Zedong’s deputy. From then on, the pattern between Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai gradually took shape.

After the Red Army arrived in Yan’an following the Long March, Mao Zedong’s leadership position within the CCP was increasingly consolidated. In October 1937, Wang Ming, who had previously been in charge of the CCP’s work, arrived in Yan’an from Moscow on the orders of the Comintern to serve as the Minister of the United Front Work Department and Secretary of the Yangtze Bureau. At that time, the party was roughly divided into three factions: the Mao faction, the doctrinaire faction, and the experiential faction. The top figure of the Mao faction was Liu Shaoqi, with a group of people under him, including Peng Zhen, Bo Yibo, and An Ziwen. The doctrinaire faction was composed of Wang Ming, Bo Gu, Zhang Wentian, Wang Jiaxiang, and others. The experiential faction was represented by Zhou Enlai and included Peng Dehuai, Chen Yi, and others.

Wang Ming’s reappearance made Mao Zedong uneasy. In September 1942, Mao Zedong initiated the Yan’an Rectification Movement, targeting the faction led by Wang Ming. Although the Rectification Movement is considered in party history as a correction of the party’s style, at most Wang Ming was criticized, but in reality, the main target of criticism was Zhou Enlai. This is because the doctrinaire faction led by Wang Ming had no foundation in the party; the real foundation was the experiential faction. However, Mao Zedong considered the experiential faction to be doctrinaire and therefore more dangerous.

During the Yan’an Rectification Movement, Zhou Enlai became a major target of criticism. He was once threatened with expulsion from the party and eventually conducted a five-day self-criticism during the rectification process. In the self-criticism, he deeply admitted that he had made serious mistakes in both thought and organization, was a representative of the experiential faction and an accomplice in doctrinaire rule, and was an obstacle to the party’s “Bolshevik transformation.”

The reason Zhou Enlai submitted to Mao Zedong was mainly that Mao indeed performed excellently in various aspects, especially in how to use the war of resistance to strengthen and develop the Communist forces. At the beginning of the war, the Communist Party had only 30,000 members, and by the end of the war, it had grown to 1.2 million. Therefore, Zhou Enlai began to realize Mao Zedong’s leadership ability and could only submit willingly.

The Yan’an Rectification Movement destroyed the doctrinaire faction, reorganized the experiential faction, and established Mao Zedong’s supreme leadership position within the CCP. After the Yan’an Rectification Movement, Mao Zedong Thought was incorporated into the CCP constitution as a guiding ideology alongside Marxism-Leninism. Zhou Enlai’s submission to Mao Zedong thus began.

However, in the early years of the CCP’s rule in 1956, a large number of unrealistic and radical goals appeared in China’s economic plans. Zhou Enlai, who was in charge of daily government affairs, participated in the “anti-advance” and thus had disagreements with Mao Zedong. Zhou Enlai said to Mao Zedong: “As Premier, I cannot agree from my conscience.” Mao Zedong was very dissatisfied with this, and from the second half of 1957, Mao Zedong publicly criticized Zhou Enlai at least 13 times within two years, stating that the “anti-advance” had vented the anger of 600 million people and made mistakes in political direction. During the “anti-advance” in 1958, Mao Zedong criticized Zhou Enlai for being only 50 meters away from being a rightist.

Zhou Enlai, despite knowing he was right on the “anti-advance” issue, still complied with Mao Zedong’s opinions and even proposed not to hold the Premier position anymore. At the second meeting of the Eighth CCP Congress, Zhou Enlai reviewed the “anti-advance” and stated that China’s decades of revolutionary and construction history showed that Chairman Mao represented the truth, and deviating from his leadership and guidance often led to losing direction, making mistakes, and harming the party and people’s interests. His mistakes also proved this point.

Although there were still doubts and challenges against Mao Zedong’s line and policies within the CCP high-level, Zhou Enlai’s viewpoint was completely aligned with Mao Zedong’s. In 1958, under Mao Zedong’s leadership, the “general line,” “Great Leap Forward,” and “People’s Communes” were proposed, resulting in a disastrous famine. Peng Dehuai, the then Vice Premier and Minister of Defense, made mild criticisms of the Great Leap Forward during the 1959 Lushan Conference and was subsequently accused of being anti-party and purged.

At the Lushan Conference, Zhou Enlai did not speak out in defense of Peng Dehuai. Li Rui once asked Zhou Enlai about his views on Peng Dehuai’s speech, and Zhou Enlai responded: “I don’t see anything.” In fact, Zhou Enlai and Peng Dehuai shared similar views on the economic situation and the issue of advance. However, Zhou Enlai thought it was inappropriate to discuss these issues at the conference, as it might turn the conference into a venting session. Therefore, Zhou Enlai did not speak at the conference, and Peng Dehuai stated that Zhou Enlai was too sophisticated.

Not only did Zhou Enlai not support Peng Dehuai, but he also actively participated in criticizing him during Peng’s difficult times. At the Standing Committee meeting, Zhou Enlai criticized Peng Dehuai, stating that Peng’s “bones are rebellious, needs to be obedient, and lacks bones, and that leading cadres also need to be obedient,” believing that only in this way could the revolution succeed.

From 1958 to 1962, the Great Leap Forward led to severe damage to China’s economy, widespread famine, and 30 million deaths due to starvation. Liu Shaoqi, the Vice Chairman of the CCP, reflected on the Great Leap Forward, criticizing it as “three parts natural disaster, seven parts man-made disaster” and had a direct debate with Mao Zedong. He told Mao Zedong directly: “Cannibalism, you and I will make it into the history books.” However, Zhou Enlai, as China’s Premier, not only did not criticize the Great Leap Forward but also ordered the cancellation of food oil supplies in rural areas and destroyed statistical evidence of starvation deaths.

In 1964, when the suffering from the Great Famine had not yet fully dissipated, Zhou Enlai personally planned and directed the grand song and dance performance “The East Is Red,” which extolled Mao Zedong and the Communist Party. The Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976 caused unprecedented damage and had a profound impact on Chinese history. Although there were constant doubts and resistance within the high ranks of the Communist Party regarding the Cultural Revolution, strong dissatisfaction was expressed during the Central Military Commission meetings in January and February 1970, and the Huairen Hall meeting at Zhongnanhai. The Cultural Revolution faction referred to these events as the “Beijing Western Hotel Uprising” and the “Huairen Hall Uprising” in February. However, Zhou Enlai, who chaired the Huairen Hall meeting, did not express any opinions during the meeting.

After Mao Zedong forgave these individuals, Zhou Enlai wrote to warn them not to cause any more trouble. He wrote stern letters to Chen Yi, Tan Zhenglin, Li Xiannian, and three others, warning them not to make mistakes again. The letter stated: “To prevent you five comrades from going astray, I am hereby warning you, not to be unprepared in words.”

In August 1970, the Communist Party convened the Ninth Central Committee Second Plenary Session. Lin Biao and Chen Boda launched a severe criticism of the Cultural Revolution faction. Lin Biao and Chen Boda’s ideas were in opposition to Mao Zedong’s concept of continuous revolution, which enraged Mao. Not only did he overthrow Chen Boda, but he also forced the military to review its mistakes. However, Lin Biao refused to review. Zhou Enlai tried to mediate between the two sides, stabilize the situation, and hoped Mao Zedong would slow down decision-making to jointly promote economic development. But when Zhou Enlai realized that Mao Zedong had decided to part ways with Lin Biao, he began to distance himself from Lin Biao and his Four Great Commanders Huang, Wu, Li, and Qiu.

After the 913 Incident when Lin Biao fled in 1971, Zhou Enlai personally announced the isolation and investigation of Huang, Wu, Li, and Qiu, and deployed and directed actions to capture Lin Biao’s confidants and control the military air force, which was believed to be pro-Lin Biao. In the later stage of the Cultural Revolution, in 1973, Deng Xiaoping made a comeback. He subsequently clashed with Jiang Qing and other Cultural Revolution factions. Mao Zedong hoped Deng Xiaoping would draft a resolution on the Cultural Revolution in the Communist Party’s Politburo, which would essentially endorse the Cultural Revolution in a 30-70 split. Deng Xiaoping refused.

Of course, for the decade-long disaster endured by the Chinese people, Zhou Enlai never uttered a single word of denial or even questioning. What people heard and saw was Zhou Enlai’s support for Mao Zedong’s power. During this period, Zhou Enlai only resisted Mao Zedong twice, and both times the resistance was due to direct attacks from Mao Zedong and his wife Jiang Qing against him, forcing him to protect himself.

Diplomatic Achievements and Challenges

In 1971, to counter the enormous pressure from the Soviet Union on China, Mao Zedong decided to re-engage with the United States. Zhou Enlai personally implemented this, and his personal charm won domestic and international praise, known as Zhou Enlai Diplomacy. Except for Mao Zedong’s groundless attacks, Mao started to criticize the Ministry of Foreign Affairs continuously from 1972 onwards, and in 1973, he criticized the Ministry of Foreign Affairs repeatedly, as it was directly under Zhou’s supervision.

Between June and July 1973, Mao Zedong issued several severe criticisms of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, saying that the alliance with the bourgeoisie often forgets to struggle, and even called the Ministry’s reports “a load of nonsense.” On July 4, 1973, during a conversation with Mao Zedong, Wang Hongwen, and Zhang Chunqiao, Mao Zedong said: “I usually do not read such critical documents, including the Premier’s speeches. Major matters are not discussed while minor matters are discussed daily. If this practice is not changed, there will inevitably be corrections, and in the future, revisionism will emerge. Don’t say I didn’t mention it in advance.”

Faced with Mao Zedong’s criticisms, Zhou Enlai constantly tried to placate him. Four months later, Mao Zedong once again wielded a big stick against Zhou Enlai. On November 13, 1973, when U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger visited China, he made a last-minute request to discuss Sino-American military cooperation with Zhou Enlai the night before he was to leave. The previous evening, after the farewell party and banquet were over, Kissinger suddenly requested a private meeting with Zhou. Kissinger suggested some degree of military cooperation between China and the U.S. because at that time, China and the U.S. had come together to counter the Soviet Union, and the U.S. could inform China of Soviet military deployments via satellite.

That evening, since Mao Zedong was already asleep, Zhou did not immediately report this to Mao. Kissinger was to leave the next morning, and Mao was asleep again, so under these circumstances, Zhou told him a live conversation. This conversation indicated that both sides could designate a person to continue discussing this issue, without any commitment, but Mao Zedong seized upon this, claiming that Zhou was surrendering to the U.S. and accepting the American nuclear umbrella. Mao Zedong erupted in fury, saying: “This Sino-American communiqué is nothing special. Some want to borrow an umbrella from us, but we do not want this umbrella, it is a nuclear umbrella. Those who want to engage in revisionism will be criticized.”

Mao Zedong instructed the Politburo of the Communist Party to convene a meeting to criticize Zhou Enlai’s rightist surrenderism in diplomacy, as well as Ye Jianying’s rightist weakness during talks with U.S. military personnel, calling it Zhou Enlai’s revisionist line issue. At the meeting, Jiang Qing accused Zhou Enlai of rightist surrenderism, claiming Zhou Enlai had betrayed the country, deceived the Chairman, and kneeled to the Americans. Zhou Enlai, unable to endure any longer, slammed the table and said to Jiang Qing: “I, Zhou Enlai, have made many mistakes in my life, but the hat of rightist surrenderism cannot be placed on my head.” This was Zhou Enlai’s first resistance to Mao Zedong since 1956. Hearing of Zhou Enlai’s resistance, Mao Zedong immediately ordered an expansion of the criticism meeting and specifically established a central help team of Politburo members to assist the Premier in recognizing mistakes. The help team ordered Zhou Enlai to write a self-criticism himself, without the help of a secretary. The criticism meeting was held at the Great Hall of the People from November 25 to December 5.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs was Zhou Enlai’s independent domain, impenetrable and impervious. Some said Zhou was extremely afraid of the Soviet Union and would act as a puppet of the Soviets if they came in. When I interviewed Qiao Guanhua back then, he said he heard from Mao that Zhou was going to be a Soviet puppet, and he used the term “hair-raising.” The tone of the Politburo’s criticism of Zhou was set according to Mao’s tone, so Zhou was later criticized for betraying the country and surrendering to the U.S., kneeling and bowing.

In 1975, Zhou was already seriously ill. Qiao Guanhua and Zhang Hanzhi visited Zhou Enlai at the 305 Hospital. Since Qiao Guanhua and Zhang Hanzhi were also attendees of the expanded Politburo meeting and needed to speak, they reviewed with Zhou. Qiao Guanhua once said to Zhou Enlai: “At that time, under such circumstances, we said some critical words to the Premier. I am expressing my apology for this inner unease.” When Zhou Enlai replied: “This matter has nothing to do with you.” Jiang Qing attempted to completely overthrow Zhou Enlai, claiming it was the 11th ideological struggle and accusing Zhou Enlai of being eager to replace the Chairman when Mao Zedong was seriously ill in early 1972. Zhou Enlai ultimately made a high-profile self-criticism according to Mao’s tone, which was considered acceptable. On December 4, 1973, during this self-criticism, Zhou Enlai also led the chant: “Learn from Comrade Jiang Qing.”

Throughout the process of criticizing Zhou, Mao never appeared publicly but manipulated the meetings from behind the scenes, sending two liaison officers, Wang Hairong and Tang Wensheng, to convey Mao’s speeches. During the first Politburo meeting criticizing Zhou, Tang Wensheng spoke for eight hours, revealing Mao’s criticisms of foreign affairs and Zhou. After Zhou Enlai’s self-criticism, on December 9, Mao Zedong finally emerged from behind the scenes and said to Zhou Enlai: “Premier, you’ve been criticized. I heard they’re having a great time criticizing you.”Mao Zedong also pointed at Wang Hairong and Tang Wensheng, saying, “They are targeting me, targeting the Premier, defecating and urinating on me.” In the future, it will be said that they targeted the Premier. Zhou Enlai narrowly escaped disaster once again.

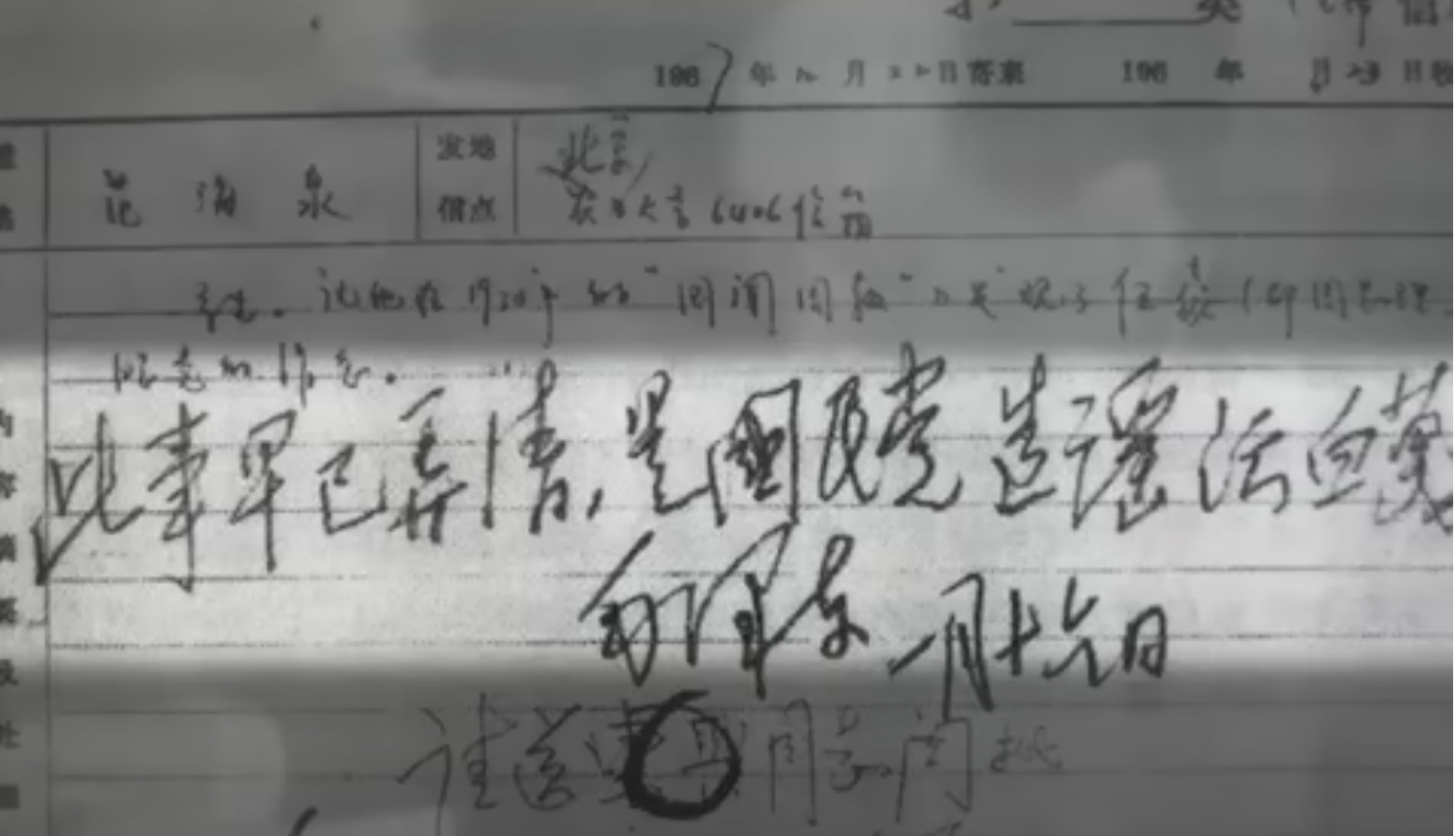

On June 16, 1975, Zhou Enlai, who had undergone three major surgeries and weighed less than 31 kilograms, wrote his final letter to Mao Zedong from his sickbed. He wrote: “From the Zunyi Conference to today, it has been exactly 40 years. Despite the Chairman’s constant guidance, I still made mistakes and even committed crimes. I am truly regretful. Now, in my illness, I repeatedly reflect and not only want to maintain my integrity but also wish to produce a decent summary of my opinions. I wish the Chairman better health. Zhou Enlai.”

On June 16, 1975, for Zhou Enlai, this standard of integrity was whether he had finally satisfied Mao Zedong. On May 21, 1966, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China issued the 516 Notice. Five days later, Zhou Enlai said at an expanded Politburo meeting, “We must follow Chairman Mao. Today, Chairman Mao is the leader, and a hundred years later, he will still be the leader. Disloyalty in old age is a disqualification.” During the Cultural Revolution, Zhou followed Mao, maintaining his integrity, which was his most important political principle during the Cultural Revolution. However, in August 1975, Mao Zedong launched the “Criticize Water Margin Movement,” saying, “The merit of ‘Water Margin’ is that it advocates surrender, serving as a negative example to make people aware of the surrenderist.” Mao Zedong’s renewed mention of surrenderism once again touched Zhou Enlai’s nerves because the issues from the Wuhou Incident and recent negotiations with the United States had brought up Zhou Enlai’s surrender problem. In fact, during the criticism of Lin Biao and the rectification campaign in 1972, the Wuhou Incident had been raised again. At that time, Chen Yun and Kang Sheng, as the parties involved, testified, “This is a plot by the Kuomintang, a forgery by Kuomintang agents, used to attack and slander our party and Premier Zhou.” On June 23, 1972, Zhou Enlai gave a special report on the Wuhou Incident at the Criticism of Lin Biao and Rectification Campaign meeting, announcing that the report and related documents would be filed according to Mao Zedong’s opinion. What was agreed upon at that time was to send it to the provincial party departments for filing, explaining Zhou’s perspective on the Wuhou Incident, but in the end, it was not sent to the provincial party officials, and the matter was dropped.

The matter remained unresolved until September 20, 1975, when Zhou underwent his final major surgery. Before entering the operating room, Zhou, already under anesthesia, spent a long time in the bathroom. Deng Yingchao wondered why he was taking so long. When she opened the door, she found Zhou sitting on the toilet, still revising. He had added to the 1972 explanation of the Wuhou Incident that it was “finally written by Zhou Enlai before entering the operating room.” He was so weak that his hands were trembling. Thus, this remained a concern for Zhou, leading to the scene described at the beginning of this article. Just before being pushed into the operating room, Zhou Enlai suddenly shouted, “I am not a surrenderist!”

Although this can be seen as Zhou Enlai’s second act of resistance against Mao Zedong to protect himself, it is more like Zhou Enlai’s helpless plea to Mao Zedong, hoping Mao would understand his loyalty and trust him. Similarly, Zhou Enlai maintained high regard and protection for Mao Zedong’s wife, Jiang Qing, for the same reason.

Zhou Enlai and Jiang Qing’s Relationship

What was their relationship like at the beginning? At first, Zhou and Jiang Qing had a rather good relationship. Especially during the wartime period, although Zhou did not often stay in Yan’an and returned occasionally, after Jiang Qing married Mao, Zhou Enlai was a very understanding and benevolent leader. So, in various situations, Zhou Enlai often interacted with Jiang Qing. Jiang Qing would also confide in Zhou Enlai. At that time, these conversations were limited to general personal matters and did not involve politics, as Mao Zedong had not yet brought Jiang Qing into political prominence.

After Mao Zedong brought Jiang Qing into the political arena, what was their relationship like? Mao Zedong brought Jiang Qing into the political arena mainly for the Cultural Revolution. Therefore, their relationship was primarily based on cooperation, with some conflicts being secondary. Mao’s Cultural Revolution actually involved a dual approach. On one hand, he wanted Jiang Qing to lead the charge for the Cultural Revolution; on the other hand, he wanted Zhou Enlai to maintain social order. Therefore, Zhou Enlai’s and Jiang Qing’s roles were different, with different emphases, rather than a struggle over policies.

At the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, Mao Zedong deliberately highlighted Jiang Qing’s political status, and Zhou Enlai dared not neglect this. On March 27, 1968, at a mass meeting of a hundred thousand people in Beijing, Zhou Enlai proactively introduced Comrade Jiang Qing’s revolutionary achievements. He said Jiang Qing had written revolutionary articles and was a close comrade of Chairman Mao and a diligent student. At this meeting, Zhou Enlai also shouted the slogan “Defend Comrade Jiang Qing with our lives.” During the Ninth Party Congress, Zhou Enlai nominated Jiang Qing to the Central Political Bureau, although before that, Jiang Qing was not even a Central Committee alternate member. In 1973, during the Tenth Party Congress, Zhou Enlai further proposed Jiang Qing for the Politburo Standing Committee, but this time, Mao Zedong blocked it.

Zhou Enlai was actually the most perceptive about the relationship between Mao Zedong and Jiang Qing within the Communist Party. He realized that the Cultural Revolution was Mao Zedong and Jiang Qing’s personal affair. Recently, in a memoir by Qiu Huizuo, an interesting incident was mentioned. After the Ninth Party Congress, Huang, Wu, Li, and Qiu, four military cadres, entered the Politburo. Zhou Enlai specifically spoke to them about how to perform well in central work. Zhou Enlai asked, “When working at the center, you need to manage your relationship with the Chairman, Vice Chairman Lin, and Comrade Jiang Qing.” He pointed out that managing the relationship with Jiang Qing was equivalent to managing the relationship with the Chairman.

To demonstrate his absolute loyalty to Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai also tolerated Jiang Qing’s demands in all respects. Wu Faxian, one of the Four Great Marshals, Deputy Chief of Staff, and Air Force Commander of the People’s Liberation Army, said that at the Central Cultural Revolution meeting, the Premier was isolated. Jiang Qing was very fierce, often slamming the table and criticizing the Premier, telling him repeatedly, “You, Zhou Enlai, should not forget that if it weren’t for me protecting you, you would have been toppled long ago.” Zhou Enlai responded, “Comrade Jiang Qing, you are stronger than me; I must learn from you.”

To avoid offending Jiang Qing, Zhou Enlai even sacrificed those closest to him. In 1968, Zhou Enlai personally approved the arrest of his own brother, Zhou Enshou. Zhou Enshou, also known as Zhou Tongyu, during the difficult period of the 1960s, held gatherings at home and discussed current politics, including Wang Guangmei’s brother Wang Guangqi. During the Cultural Revolution, these materials were brought out by Jiang Qing and handed over to Zhou Enlai. Thus, Zhou Enlai immediately arrested Zhou Tongyu. Although later revelations showed that Zhou Enlai was concerned about his brother being persecuted by the Red Guards and had him arrested by Beijing’s security district to protect him, Zhou Tongyu was still imprisoned for seven years, unable to read newspapers or listen to the radio, and was not released until May 1975.

Similarly, in 1968, Zhou Enlai’s adopted daughter, Sun Weishi, was falsely accused by Jiang Qing and imprisoned. Sun Weishi was a legendary woman and a prominent figure with complex relationships with the four major leaders of the Communist Party: Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, Zhu De, and Lin Biao, making her a victim of the most powerful women in the Cultural Revolution, Jiang Qing and Ye Qun. According to a later account by a member of Sun Weishi’s case team, Jiang Qing once told the case team members, “Sun Weishi is a femme fatale, a vixen, a time bomb sleeping next to the Chairman.”

In October 1968, Sun Weishi was persecuted to death in a labor camp. Whether her representative decree was signed by Zhou Enlai, Zhou Binde, Zhou’s niece, stated that Sun Weishi and her father Zhou Tongyu (i.e., Zhou Enshou) were both approved by Zhou Enlai personally. Ruan Ming, who served as Deputy Director of the Theoretical Research Office at the Central Party School of the Communist Party of China, wrote in an article in 1994 that when investigating the crimes of the Gang of Four, it was discovered that many of the unjust cases persecuted during the Cultural Revolution had Zhou Enlai’s signature on the arrest warrants. At that time, especially in Beijing, arrests had to be approved by the Central Cultural Revolution Meeting, and Zhou Enlai was the leader of this meeting, so all matters had to be reviewed by him.

Cheng Yuangong, Zhou Enlai’s bodyguard who had been with him for decades, inadvertently offended Jiang Qing in March 1968, leading Jiang Qing to demand Cheng’s arrest. Deng Yingchao, on behalf of Zhou Enlai, told Wang Dongxing, “We must arrest Cheng Yuangong to show that we have no selfish motives.” Thus, Cheng Yuangong was sent to a “Five-Seven” cadre school under Jiang Qing’s faction, where he remained for nearly eight years.

In May 1972, Zhou Enlai was diagnosed with bladder cancer. From that time, Zhou underwent more than a dozen surgeries of various sizes. However, even during Zhou Enlai’s severe illness and hospitalization, Mao Zedong never visited him. Nonetheless, Zhou Enlai’s loyalty to Mao Zedong remained unchanged. In Zhou Enlai’s final days, Ye Jianying, who visited Zhou daily at the hospital, had a final conversation with him. Zhou Enlai’s guards recalled that Ye Jianying had all the guards and medical staff leave the room. What Ye Jianying and Zhou Enlai discussed remains unknown. However, Ye Jianying later mentioned that many people within the Party came to him, suggesting taking action to arrest the Gang of Four. Ye Jianying tested Zhou Enlai’s response, and Zhou Enlai said, “We should still trust Chairman Mao and listen to his words.” Ye Jianying said Zhou Enlai was reluctant to discuss the matter.

On January 8, 1976, Zhou Enlai passed away. On January 11, as Zhou Enlai’s hearse was heading to Babaoshan, millions of people in Beijing spontaneously lined Chang’an Street to bid farewell to him, creating a stunning scene. The Central Committee decided that Zhou Enlai’s memorial service would be held on January 15. Whether Mao Zedong could attend was judged by Mao’s medical team. Their assessment was that Mao could attend Zhou Enlai’s memorial service without being affected, and it was best to limit the time to within one and a half hours. These details are officially recorded. The Politburo made preparations, including the route and stretcher. The memorial service was even postponed to wait for Mao. But at the last moment, Mao, through Wang Dongxing, sent a message saying, “I will not go, just sending a wreath.”

Even Zhang Yufeng could not tolerate this. It is said that Zhang, in tears, begged Mao to attend, but Mao still did not go. On January 15, 1976, the memorial service for Zhou Enlai, Vice Chairman of the Communist Party of China and Premier of the State Council, was held at the Great Hall of the People. Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Communist Party of China and Zhou Enlai’s colleague for over half a century, did not attend.

Since 1949, China has experienced countless movements: agricultural cooperatives, people’s communes, anti-rightist campaigns, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution. Nowadays, cooperatives and people’s communes no longer exist; over 99% of rightists have been rehabilitated. The Great Leap Forward caused a famine, which is an undisputed fact; the Cultural Revolution is recognized as a decade-long catastrophe.

Conclusion

These movements inflicted immeasurable harm on the Chinese people. High-ranking Communist Party leaders such as Peng Dehuai, Liu Shaoqi, Lin Biao, and Deng Xiaoping had all opposed Mao Zedong to some extent and paid a heavy price for it. However, Zhou Enlai never took any actions of resistance. For Zhou Enlai’s inaction, the Chinese official stance also acknowledges that Zhou Enlai said and did things against his own beliefs, only to justify them as sacrificing for the greater good and bearing humiliation. Can this be considered as covering up the past mistakes?

Related Content

- The Untold Story of Zhou Enlai:The Face Behind the Political Paragon (Part 2)

- The Untold Story of Zhou Enlai:The Face Behind the Political Paragon (Part 1)

- Mao Zedong and Lin Biao:The Mystery of the First Faction's Defection(Part 4)

- Mao Zedong and Lin Biao:The Mystery of the First Faction's Defection(Part 3)

- Mao Zedong and Lin Biao:The Mystery of the First Faction's Defection(Part 2)